Frequently Asked Questions

This document has

the following sections:

-

Section 1 – What is the story?

-

Section 2 – Knowing the military service in Iran

-

Section 3 – IRGC travel ban - extent of impacts

-

Section 4 - Personal stories, what happened to the families

-

Section 5 - What is done in the United States?

-

Section 6 - What is done by the conscripts?

Section 1 - What is the story?

This section answers general questions around what the story is and why some Iranian conscripts are refused entering the United States and are subject to extreme screening in the airports to the other destinations.

- 10000 – What is changed in April 2019?

o 10020 - FTO (Foreign Terrorist Organization) list and the ramification around memberships

o 10050 - How come this law is applicable to the past (retrospectively)?

- 10100 – Inadmissibility at the US borders

o 10110 - Does it affect all IRGC conscripts?

o 10120 - What happens at the US border at the first encounter

o 10130 - The role and importance of the “Officer’s discretion”

o 10140 - What is the law around inadmissibility

o 10150 - What about individuals other than Canadian citizen conscripts

o 10160 - Documents provided by CBP

o 10170 - How CBP knows about the history of military service of travelers?

- 10200 – Impact on the family and friends

- 10300 – What happens to non-Canadians Iranians? Non-IRGC conscripts?

10000 - What is changed in April 2019?

● On April 15, 2019, IRGC is added to the FTO (Foreign Terrorist Organization) list by the US Department of State.

o

https://2017-2021.state.gov/designation-of-the-islamic-revolutionary-guard-corps/index.html

● 10020 - FTO and the ramification around memberships

o FTO list: https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations/

o It is unlawful for a person in the United States or subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to knowingly provide “material support or resources” to a designated FTO

o There is a wide range of ramifications, including a travel ban for aliens:

▪ Representatives and members of a designated FTO, if they are aliens, are inadmissible to and, in certain circumstances, removable from the United States (see 8 U.S.C. §§ 1182 (a)(3)(B)(i)(IV)-(V), 1227 (a)(1)(A))

●

10050 - How come this law is applicable to the past (retrospectively)?

o

The law is

not applicable to the past. To better know the situation please review three

tiers of TRIG:

▪

https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/other-resources/terrorism-related-inadmissibility-grounds-trig

o

Designating

an organization as tier I and II has a formal process by the secretary of

state.

o

Tier III

can be assigned by many parts of the US government and does not have an

official list.

o The US secretary of State claims that IRGC was in tier III since 1985, so any affiliation since then is considered membership of an FTO today.

o Any affiliation with IRGC (voluntary or not) will be considered as a tie to IRGC

10100 - Inadmissibility at the US borders

●

10110 - Does

it affect all IRGC conscripts?

o

All Iranian travelers to US could be potentially stopped

and questioned because of any of the following reasons:

▪

Random

check

▪

Previous US visa request (visitor, work permit, immigration, …)

▪

Relation to other inadmissible persons

▪

Traveling

with former IRGC conscript

●

10120 - What

happens at the US border on the first encounter

o

After your

name being flagged by the first CBP officer, you

will be directed to the secondary screening and the following steps will

happen, less or more:

▪ You should expect questions about yourselves, starting from your past life in Iran, family, current job, education, any affiliation with any military organizations and your sources of income back in Iran.

▪ once it gets to questions about your conscription status, you have to provide more details about your branch, rank, your position, your job, how long you served, have you had any military training, if you claim that you were not be conscripted at IRGC, they will ask for military service ID card, preferably translated in English. CBP officers are familiar with the different types and branches of military forces in Iran. They know the new format of military cards versus the old format. The traveler must provide the old version of the military card showing the exact type of force they served in.

▪ The next set of questions are about your current trip, where are you going, purpose of trip, who paid for your trip, who is hosting you in the US, date of return, and who is accompanying you.

▪ If you are traveling with a family member or friend (especially if you are on the same booking), they will be asked the same questions as well as your relationship and why you are traveling together

▪ Biometric is the next step, fingerprint has been the most common one; they may take photos as well.

▪ Rarely, you might be asked to hand your cellphone to check as well, same with your wallet and your credit cards

o Once the officer decides not to let you in:

▪ They will offer you to voluntary withdraw and go back home (They will most probably return the whole family)

▪ They may also hand over you the I-275 form, see below link for details:

▪ In some cases, stamping on the passport and rejecting your entry request is also an option.

●

10130 - The

role and importance of the “Officer’s discretion”

o Entering the US is not a right. It is up to the CBP officer to decide if you are allowed to enter the US (even if you have an entry visa). It is completely at the officer’s discretion to decide how much details to be asked or documents to be requested to have a firm decision. There are some protocols in place engaging CBP, FBI and a couple of other organizations to make the decision. This process may take hours. As mentioned before, having a US visa does not provide a right to the visa holder to enter the US. Any small clue or suspicious that a person might be connected to any illegal or terrorist-related organization or activity is enough for the officer to refuse the admission. A CBP Officer does not need to have firm evidence to make the decision.

o So, the experiences and the depth of questioning could be different per traveler, officer, and border. Land border officers in some cities have kinder behaviors than others but the outcome is almost the same.

o There are instances that FBI officers at the border help CBP to gather documents or conduct the requisition. Multiple security related organizations work together to help CBP officers make the best decision.

●

10140 - What

is the law around inadmissibility:

o

Reference to INA act

▪

https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/legislation/immigration-and-nationality-act

▪

https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title8-section1182&num=0&edition=prelim

o

Which section of INA is applied to these inadmissible

individuals?

▪

Based on

the information we gathered so far INA212(a)(7)(A)(i)(I)

is the most common section of the act that

has been referred to, which is

technically not the section that has anything to do with terrorism activities

▪

We assume the

officers use the safest approach in providing the inadmissibility reason. This

will make it easier for them to not necessarily prove any wrong and at the same

time introduce us to the less severe consequences

●

10150 - What

about individuals other than Canadian citizen

conscripts:

o

Official

members of IRGC (staff and voluntary

members-Basij)

▪ Travelers might be stopped and checked based on a reasoning explained in #11110.

▪ IRGC officials not satisfying any of those criteria and have not served their mandatory service in IRGC are not easily detectable by the officers, see https://youtu.be/TdQHjvzBf44?t=10912

o

What about well-known IRGC members living in the US?

▪ The travel ban is not applicable to the United States citizens (ref. #10000). US citizens cannot be easily banned from entering their home country. So, regardless of their status of military service, these checks are not applicable to the US citizens.

o

Canadian Nexus card holders are not excluded from this

process. There are cases that nexus cards got canceled

after or even before inadmissibility

●

10160 - Documents

provided by CBP:

o

What is FOIA? How to apply? Repeal process?

▪

[UPDATE] as of December 2022, CBP detailed information

cannot be obtained through FOIA. Requests to be made directly to the CBP.

▪

FOIA

(Freedom of Information Act) allows anyone to ask for their information

gathered or recorded by the government of the United States.

▪ Request: Requests on CBP records can be made through https://www.foia.gov/. Reports will be shared through the same web-based system.

▪ Repeal: In some cases, the provided report does not have the full records, may contain wrongly documented information or having some parts redacted. There is a repeal process to correct the mistakes or ask for full information.

●

10170 - How

CBP knows about the history of military service of travelers?

o

Are the US and Canada sharing security information?

▪ There are some contracts in place and multiple common databases that US and Canada share to protect themselves against terrorism:

o TUSCAN:

▪ https://globalnews.ca/news/4290088/canada-u-s-terror-sharing-list-privacy/

o Canada No-fly list:

▪ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/30/canada-us-tuscan-database-no-fly-list-trudeau

o Australia and UK have some collaboration with US and Canada in this regard

▪

▪ Generally, Canada relies on the information, systems and databases provided by the United States to protect its borders.

o

How Canada knows the military service background of each

Canadian

▪ Provided at the time of requesting for any visa (including immigration visa)

o

Those who

claim they were not conscripted by IRGC might be asked for their military

service ID card and in case the traveler don’t present it, the officers might:

▪ return the traveler home, inadmissible

▪ Let the traveler enter the US conditionally for this time but traveler must present the ID in the next trip

▪ Let the traveler enter the US with no condition

10200 - Impact on the family and friends

●

All your

accompanying travelers, especially those who are on the same flight booking

reference will highly likely end up in the same inadmissibility situation

●

There are

also cases that persons with links through phone

book, social media, and other means are also stopped, questioned and

sometimes refused admission.

10300 - What happens to non-Canadians Iranians? Non-IRGC conscripts?

●

(10310) PR holders

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10320) Iranians with work permit (Flag poling)?

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10330) Iranian

students traveling to US

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10340) Iranian with

green card in US

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10350) Iranian

investors traveling to US

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10360) Canadian

served in Army (Artesh) or Police (Naja)

o [Not completed - Work in progress]

●

(10370) Other

countries citizens:

o

https://www.bbc.com/persian/world-59906672

Section 2 – Knowing the military service in Iran

This section covers questions around the details of mandatory military service in Iran.

Subsections are:

- 20100 – General Overview of the military service

- 20200 – Branches and divisions of Iranian military system

- 20300 – Duration of mandatory military service

- 20400 – Ranks, salary and conditions

- 20500 – Military service exemptions

- 20600 – Buying out the military service

- 20700 – Consequences of the mandatory service refusal

- 20800 – Completion of mandatory military service

20100 - General Overview of the military service

●

All males of the required age are subject to the draft in

Iran, however there are exceptions for those who cannot serve on account of

physical or mental health problems or disabilities. (Ref: #20930: section 5.1.1, #20940: sections 1.2.1, 2.4.1)

●

Sources indicate that military service is mandatory for all

males in Iran (IHRDC 7 Nov. 2013; Al-Monitor 19 Dec. 2013; Human Rights Watch

Dec. 2010, 23). The US CIA World Factbook states that, as of 2012, the age of

compulsory military service for men in Iran is 18 (US 26 Feb. 2014). (Ref: #20910)

●

US CIA World Factbook states that volunteers start at 16

(US 26 Feb. 2014). Sources state that, the recruitment age of the Basij Forces

["a paramilitary volunteer militia" (Al Jazeera 24 Apr. 2012)] is 15

(Ref: #20910)

● According to the December 2013 General Official Report of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs: ‘Students are eligible for deferment of military service. They are expected to enter military service within six months after finishing their studies. In practice, this period can be extended due to administrative delays. (Ref: #20930, section 7.1.1)

20200 - Branches and divisions of Iranian military system

●

20210 - The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World

Factbook indicates that the military branches in Iran in 2011 consisted of the

: Islamic Republic of Iran Regular Forces (Artesh): Ground Forces, Navy, Air

Force (IRIAF), Khatemolanbia Air Defense Headquarters; Islamic Revolutionary

Guard Corps (Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, IRGC): Ground Resistance

Forces, Navy, Aerospace Force, Quds Force (special operations); Law Enforcement

Forces. (US 26 Feb. 2014) (Ref: #20910)

●

20220 - According to a 2019 report by the US Department

Intelligence Agency (DIA), Iran’s armed forces is comprised of the (Ref: #20940, section 4.1.1):

o

Artesh (Farsi for ‘army’), consisting of Ground Force,

Navy, Air Force, Air Defense Force, estimated 420,000 personnel

o

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), consisting of

Ground Force, Navy, Aerospace Force, Qods Force, Basij, estimated 640,000

personnel, including 450,000 Basij (reserves)

o

Law Enforcement Force, the national police force (commonly

referred to by its Farsi acronym NAJA6), estimated 200,000 to 300,000

personnel7

●

20240 - Conscripts reportedly comprised more than 50

percent of the IRGC (most volunteers were reportedly recruited from the Basij

Forces).’9 The same source described the Basij as a ‘… volunteer paramilitary

group with local organizations across the country, which sometimes acts as an

auxiliary law enforcement unit subordinate to IRGC ground forces (Ref: #20940: section

4.1.3)

●

20250 - The Washington Post wrote in February 2021 that

conscripts were ‘… not allowed to select which branch of the military they

enter. Iranian officials have said that roughly 400,000 men show up for their

compulsory service each year and are sent to either the army, a law enforcement

agency or the IRGC.’ (Ref: #20940: sections 5.2.3, 5.2.4). The DFAT report noted that ‘One

cannot choose in which force and geographic location to undertake military

service.’ (Ref: #20940:

section 7.1.1)

20300 - Duration of mandatory military service

●

Sources indicate that the duration of compulsory military

service ranges from 18 to 24 months (BBC 26 Dec. 2013; Al-Monitor 19 Dec.

2013). According to two sources, the length of service depends on the

geographical location of the conscript (IHRDC 7 Nov. 2013; BBC 26 Dec. 2013).

The BBC reports that, according to Iranian Students' News Agency (ISNA),

General Musa Kamali, the Vice Commander of the Headquarters for Human Resources

of the Iranian Armed Forces, was quoted as saying that "the duration of military

service is 18 months in combat and in insecure regions, 19 months in the

regions which are deprived of facilities and have bad weather conditions, 21

months in other places, and 24 months in government offices" ( 26 Dec.

2013) (Ref: #20910)

20400 - Ranks, salary, training and conditions

●

20410 - Rank insignia of the Iranian Military:

o

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rank_insignia_of_the_Iranian_military

o

Conscripts receive assigned ranks based on their education.

During their service, a conscript’s rank normally does not change.

o

The highest rank assigned to a conscript is changed

multiple times in the last decades but generally the highest rank assigned to

the Doctors, PhDs, Masters and equal is “First Lieutenant”. Bachelors and equal

receive “Second Lieutenant”. College and equal degrees would receive “Third Lieutenant”

rank. High school diploma and others would receive “Private” to “Sergeant”

ranks. These rules changed multiple times but it is almost the same as above.

●

20430 - Salary: Conscripts receive a low payment of around

$1 per day ($30USD per month) (Ref: #20930: section 8.1.1) Salaries

are low, although in March 2022 it was reported that pay was doubled to US$100

(£88.50) per month (Ref: #20940: section 2.4.9)

●

20440 - Conditions for conscripts in Iran are reported to

be poor with poor pay, low morale, poor living conditions and

malnutrition. There have been reports of harassment and abuse of conscripts due

to their faith, leading to self-harm and suicide, including in suspicious

circumstances. However, in general, the conditions and/or treatment likely to

be faced by a person required to undertake compulsory military service would

not be so harsh as to amount to a real risk of serious harm (Ref: #20930, section

2.4.8)

●

20450 - Specific military training is limited and that

tasks may involve activities such as office work, gardening, driving, cleaning

and labouring. Educated and talented conscripts can serve at knowledge-based

companies. There is no evidence to indicate conscripts are likely to be

involved in acts contrary to the basic rules of human conduct whilst performing

military service in Iran (Ref: #20940: section 2.4.6) Sina Azodi wrote that ‘Since the Iran-Iraq

War ended in 1988, most Iranian conscripts have seen no combat, and their

military service is often devoid of actual combat training.’ (Ref: #20940: section 7.1.5)

20500 - Military service exemptions

●

There are multiple situations that a male person could be

exempt from the military service including, the only caretaker of the family,

only son when the father is older than 65, active members of Basij, those who

work in industries vital to the government or military, exceptional scholastic

achievement, medical exceptions, sexual minorities and more. Please refer to #20910 and #20940 section 2.4.2.

20600 - Buying out the military service

●

There were short periods that buy out option was available

for male persons within special conditions, mainly draftees living out of the

country.

●

General Kamali reportedly added that "for those who

live outside of the country, the option of paying off military service had been

cancelled earlier this year. For those who live in the country, paying to avoid

military service has not always been offered" (Al-Monitor 19 Dec. 2013).

Further information about payment in lieu of compulsory military service could

not be found among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate within the

time constraints of this Response. (Ref: #20920)

20700 - Consequences of the mandatory service refusal

●

20710 - Draft evaders are liable for prosecution. A person who deserts from the army will have

to continue military service upon return if he is under the age of 40. Evading

military service for up to a year during peace time or 2 months during war can

result in between 3 and 6 months added to a person’s military service. Longer

draft evasion (more than 1 year in peacetime or 2 or more months during war)

may result in criminal prosecution. (Ref: #20930, section 2.4.11)

●

20720 - If the draftee is absent for longer than three

months during peace time (or 15 days during war), the military service will be

extended by six months. Longer draft evasion (one year during peace or two

months during war) may result in criminal proceedings before a military court.

Draft evaders risk losing social benefits and civic rights including

their right to work, to education or the right to set up a

business. If a draft evader evaded reports for military service

voluntarily, the duration of service will be extended by three months, whereas

if a draft evader is arrested, he is obliged to serve for an extra six months.

(Ref: #20930, section 7.2.2)

●

20730 - Sources state that people who refuse military

service cannot get a passport (IHRDC 7 Nov. 2013; Al-Monitor 19 Dec. 2013). The

IHRDC adds that failing to serve without an exemption can also result in

"a ban on ... leaving the country without special permission" (7 Nov.

2013). Sources note that refusing to serve in the army without an exemption can

result in not being granted a driver's license (IHRDC 7 Nov. 2013; Human Rights

Watch Dec. 2010, 23). (Ref: #20910, section 4)

●

20740 - Deserters may face imprisonment or, depending on

their intentions, considered as mohareb (a person who commits moharebeh,

defined as drawing a weapon on the life, property or chastity of people or to

cause terror as it creates the atmosphere of insecurity), which can invoke the

death penalty. However, there is no indication that such penalties against

deserters occur in practice (Ref: #20940: section 2.4.13)

●

20750 - The DFAT report stated that ‘Draft evaders may lose

social benefits and civic rights, including access to government jobs and

higher education, and the right to establish a business. The government may

also refuse to grant draft evaders drivers licences, revoke their passports or

prohibit them from leaving the country without special permission...’ (Ref: #20940: sections

8.3.1, 8.3.2)

20800 - Completion of mandatory military service

A completion card will be issued when the conscript finishes the duration of service.

●

Old military card versus new military card

o

Military card formats has changed in the last years. The

new card format does not show the organization that the conscript served at

(Army / IRGC / Police)

●

What if a male Iranian has never had the military card?

o

Not having a military card means the person is still

deferring the service because of the study permit or evaded the service.

●

Exemption cards: The

US State Department Bureau of Consular Affairs Iran Reciprocity Schedule noted

that: ‘Because military service is mandatory, Iranian men over 18 who were

exempt from military service will have exemption cards issued by the General

Conscription Department of the Police Force (Niroo-e Intizami Jumhoori-e Islami

). (Ref: #20930, section 5.5.1)

●

According to the USSD Bureau of Consular Affairs

Reciprocity Schedule, ‘Kart-e Sarbazi (military card); Kart-e Payan-e Khedmat

doreye Zaroorat (service completion card); or Kart-e Mo’afiyat az khedmate

doreye zaroorat (exemption card)’ are issued by the ‘Iranian Public

Conscription Organization (since 1980), under the Law Enforcement Force of the

Islamic Republic of Iran (NAJA); [or] Imperial Armed Forces (before 1980).’

(Ref #20940: section 5.4.1)

20900 – References

●

20910 - Immigration

and Refugee Board of Canada (March 28, 2014):

o

https://irb.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=455219&pls=1

●

20920 –

European COI (Country of Origin) guide:

o

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1345230/iran-country-policy-info-note-military-service.doc

●

20930 – Immigration

and Refugee Board of Canada :

o

https://www.refworld.org/country,COI,IRBC,,IRN,,550fd7e64,0.html

●

20940 – United Kingdom (Country of Origin) guide, Nov. 2022:

Section 3 – IRGC travel ban - extent of impacts

This section explains the extent of the

inadmissibility issue especially related to travel to other parts of the world.

This section includes:

-

30000 – Entering the United States

-

30100 – Flights to/from North America

-

30200 – Risk of inadmissibility to other countries

-

30300 – How could it be different traveling to each

country?

-

30400 – What happens in the Canadian domestic flights

-

30500 – Hints to have a better experience when traveling

to other countries

-

30700 – What may happen in Canada for Canadian Citizens?

-

30800 – What if IRGC comes out of the FTO?

30000 - Entering the United States

●

Any attempt by an inadmissible person to enter the US

(through land, air or sea) would be technically considered an intrusion.

Intruders would be treated differently and may face consequences from “Removal

order” to “long-term ban”

●

Please note that at some borders the security gate is inside

the United States.

●

The severity of the US border officials’ reaction depends

on what they have on file for each person, the level of national security at

that moment and of course the officer’s discretion.

30100 - Flights to/from North America

● Who will be impacted:

o Anyone who got inadmissible at the border before

o Groups in the same itinerary with an inadmissible person

o People living in the same address

●

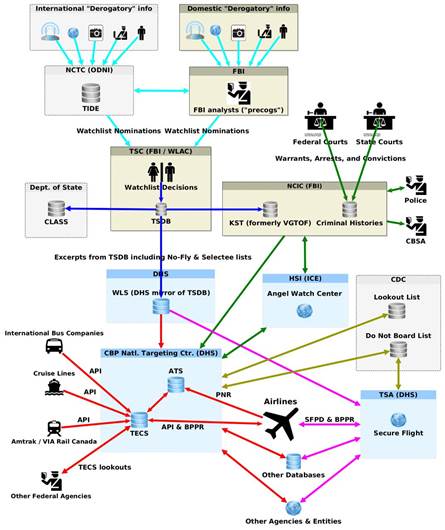

Lists and databases [Work in

progress here]

o

Different types of lists (Alert list, watch list, no fly

list , Selectee, …)

o

Different databases and their interconnection (Please refer

to #10170)

●

30130 -

Three types of problems:

o

Boarding pass

▪

Online and kiosk check-in would probably fail

▪

Check-in and security checks need more time than usual

▪

Normal check-in employees cannot print the boarding pass.

Ask for the supervisor.

▪

Supervisor must make a call to clear the passenger (it

needs between 20min to 60min)

▪

The boarding pass will have quad S

▪

Online check-in, Kiosk Check-in, Counter check-in

o

Security check

▪

Secondary screening checks and probes all belongings

o

Entering the destination country

▪

Normally, the destination country does not add any extra

steps. Mexico was an exception having thorough security check, interrogation,

and a few rejection cases.

●

30140 -

What is Quad S (SSSS)?

o

Quad S (SSSS) is the abbreviation for secondary security

screening selection. Simply put, an “SSSS” on your boarding pass means that

you’re getting an extra thorough search when you go through security.

o

Quad S can be because of unusual itinerary (flights booked

last minute, international one-way tickets, travel originating in

“high-risk” countries), being on a watch list, name similarities or

completely random. In this context, quad S is because of being on one of the

watch lists.

● 30150 – Why extra security when the flight does not have anything to do with the United States?

o All flights passing through the United States air space, or getting close enough to the air space to pose a threat of an attack or emergency landing are required to check the extra security for enlisted passengers.

o US air space (map to be added)

●

What happens when returning to Canada:

o

CBSA will put codes on the declaration form (like @@)

o

May be escalated to the superintendent

o

CBSA officers ask questions. You can explain the military

service situation.

o

Passenger need to be cleared. Officers may clear the

passenger by examination, phone calls, or asking questions.

o

May take 5 to 20 mins

30200 - Risk of inadmissibility to other countries

●

So far, only Mexico had a couple of rejections because of

the military service history. We have no evidence showing any other country may

have done the same.

30300 - How could it be different traveling to each country?

●

Iran: Nothing aside that quad S and @@ on return

●

Europe (UK, Germany, Italy, Turkey): Nothing aside that

quad S and @@ on return

●

Caribbean (Mexico, Costa Rica, Cuba, Venezuela, …) Mexico

was different (Please refer to #30200). Others are quite the same as European countries.

●

Asia (Japan): Same as European countries.

30400 - What happens in the Canadian domestic flights

●

Domestic flights in Canada do not check the international

security lists, so no extra check would happen in domestic flights. Please keep

in mind that if you are using a domestic flight to connect to an international,

then the security could happen at the source before the domestic flight can

board the passenger.

30500 - Hints to have a better experience when traveling to other countries

●

Buy a separate itinerary from other family members

●

Be at the airport 3 to 4 hours ahead of the boarding time

●

Directly ask to talk to the supervisor at the check-in

kiosk

●

Tell the supervisor that a call should be made to clear

you. Don’t need to explain inadmissibility or military service details.

●

Try not to have any check-in baggage

●

Be prepared for through examination and security screening

●

On return to Canada, ask for the superintendent. Explain

the military service and the issues.

●

Ref (T:202211041732)

30700 - What may happen in Canada for Canadian Citizens?

[Work in

progress]

30800 - What if IRGC comes out of the FTO?

●

The travel ban and quad S issues will not disappear

automatically. The lists are shared between many databases (in different

countries). Clearing it all requires a case-by-case approach which every individual

might need to follow. Multiple security systems keep the inadmissible persons’

names for different reasons. Each one requires a separate process to clear.

Section 4 - Personal stories, what happened to the families

[Not completed - Work in progress]

Section 5 - What is done in the United States?

[Not

completed - Work in progress]

Section 6 - What is done by the conscripts?

[Not completed - Work in progress]

V 2.0 – Last updated: 202212071517